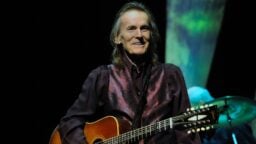

You’ll recognize the gentleman representing indie publisher Round Hill in its shock new legal battle against TuneCore; he’s featured at the top of MBW’s newsletter very recently via this Rolling Stone profile.

US-based attorney Richard Busch, Head of Entertainment at law firm King & Ballow, is infamous for suing leading publishers and songwriters for copyright infringement – including the likes of Ed Sheeran, James Arthur, Travis Scott and, most famously, Pharrell Williams and Robin Thicke.

Yet Busch has also done history-making work on behalf of prominent indie rights-holders. For example, he represented Eminem production house FBT Productions in its long-running legal battle over ‘license vs. sale’ download royalties against Universal Music Group (settled out of court in 2012).

Right now, Busch is on the attack against Spotify and the Harry Fox Agency, representing an independent publisher of Eminem songs, Eight Mile Style.

And it’s here where things get interesting in relation to Round Hill’s $32.85m lawsuit against TuneCore and its parent, Believe.

Eight Mile Style argues that Spotify did not obtain the required mechanical licenses – “direct, affiliate, implied, or compulsory” – to reproduce and distribute 243 songs performed by Eminem on its platform.

It’s also alleging that HFA and Spotify jointly conspired to “conceal Spotify’s failure to acquire timely compulsory mechanical licenses”. (It goes without saying that, at this stage, these allegations are yet to be tested by the fullness of the US legal system.)

Sound familiar? Similar (though not identical) allegations are now being made by Round Hill against TuneCore and Believe, essentially over the latter’s indie artist clients uploading to the internet cover versions of songs owned by Round Hill.

The publisher’s lawsuit, regarding 219 allegedly infringed compositions, reads: “Defendants have failed to account to or pay to Round Hill the mechanical royalties to which it would have been entitled had Defendants secured licenses for: 1) the reproduction and/or distribution of the Round Hill Compositions to Third-Party Companies; 2) the reproduction and/or distribution to third parties by Third-Party Companies at Defendants’ direction; and (3) the reproduction and/or distribution of the Round Hill Compositions on their own servers with server copies.”

The big difference between the Eight Mile Style case and the Round Hill case is that, in the latter example, a music publisher is accusing an indie distributor of the infringement of mechanical rights; in the former case, a music publisher is accusing a streaming service of a very similar violation.

Pertinent to this crucial differentiation is the fact that Round Hill (and Richard Busch’s) new lawsuit focuses solely on TuneCore’s distribution of said cover versions to download services (namely Apple iTunes, Amazon MP3, eMusic “and more”) rather than streaming services. This is no doubt deliberate.

Richard Busch is a long way from the most popular man in music, but he’s effective and – in the eyes of his clients – prolifically successful. Especially when it comes to brow-beating music industry Goliaths into settling out of court with his clients, presumably with large payments as part of the deal. (Ed Sheeran did so; James Arthur did so; Universal did so; many others have done so.)

Busch’s experience with mechanical rights-centered cases doesn’t stop at Eight Mile Style vs. Spotify, either.

In July 2017, he represented two plaintiffs, songwriter Bob Gaudio and indie publishing admin outfit Bluewater Music Services Corporation, in another lawsuit against Spotify.

This suit alleged that, between Gaudio and Bluewater, Spotify had willfully infringed the mechanical licenses of thousands of songs.

In plain language that will now be very familiar to TuneCore and Believe, the plaintiffs, represented by Busch, claimed that Spotify had “knowingly reproduc[ed] and distribut[ed] musical compositions without the licenses necessary [to do so]”.

Another relevant hallmark of the Gaudio/Bluewater vs. Spotify lawsuit: Busch cited proof of infringement had been discovered (and delivered to Spotify) thanks to the technology of Audiam – the mechanical rights identification and royalty collection platform founded by Jeff Price and now owned by Canadian collection society SOCAN.

In the Round Hill vs. TuneCore/Believe suit, Audiam’s name pops up a number of times. (Round Hill alleges that TuneCore “knowingly continued [its] infringing exploitation for years after having full knowledge that the Round Hill Compositions were not licensed after notification was provided by Round Hill and its authorized agent Audiam”.)

It took until August 2019, and literally hundreds of legal filings, for the Court for the Middle District of Tennessee to dismiss the Gaudio/Bluewater vs. Spotify cases “with prejudice”… suggesting that Richard Busch (and his clients) had once again reached a private settlement out of court with Spotify – another music industry heavyweight.

The big worry for DIY distributors now, then: What if Round Hill is successful in its suit against Believe/TuneCore – which, remember, claims to distribute over a third of all the digital music in the world?

We mean successful either with a verdict, or with a handsome out-of-court settlement (Richard Busch’s speciality)?

Will music publishers, currently feeling the crunch of COVID-hit sync and performance revenues, be tempted to file more of these lawsuits against the likes of TuneCore and its myriad rivals?

Or will those same music publishers decide that this kind of intra-industry bad blood doesn’t service the greater health of the music business?

Whisper it, but there are publishers out there whose catalogs dwarf that of Round Hill.

One concern at the heart of all of this: What protections do large-scale indie distribution services actually have against hordes of DIY artist clients uploading cover versions of owned compositions to digital platforms? (Particularly, it would seem from Round Hill’s filing, if they’re being uploaded to digital download platforms?)

Lest we forget that TuneCore alone distributes the work of over 250,000 artists.

One interesting (tempting?) element of any potential publishers vs. distributors litigation outbreak is the simple fact that the DIY artist space is the fastest-growing area, percentage-wise, of the modern global record business.

Earlier this year, Raine Group put a number on it, forecasting that (in a pre-COVID world), the “self-upload” sector alone would generate some $1.22bn in 2020.

Midia Research estimated this same DIY artist sector generated $873m from recorded music alone in 2019.

No doubt Richard Busch would argue – as he has before – that he detects moral injustice in the alleged infringement of Round Hill’s works on this occasion.

But we should be under no illusion that he’s also aware – with TuneCore paying out more than $1m to its DIY artist clients every day – that there’s serious money at stake here, too.Music Business Worldwide